In classical Chinese painting, copying the classics is an essential step in mastering one’s craft. This painting is Zhang’s vibrant copy of the masterpiece Night Revels of Han Xizai.

In classical Chinese painting, copying the classics is an essential step in mastering one’s craft. This painting is Zhang’s vibrant copy of the masterpiece Night Revels of Han Xizai.

What’s so foreign to me is not their dress from another time — it’s their adoration. They stand, sit, soaking in the artist’s plucks of the pipa, reverberating a culture kissed by gods for many millenia.

One man in a chair, listening with a sincerity, a respect, that could quell any storm; a young girl’s grace, her presence, perfect; others, hands clasped over hearts, leaning, swaying, moved by the beauty of those four strings — I’m captivated by their spirit. It’s quite a painting.

World renowned classical Chinese painter Cuiying Zhang believes that she must cultivate her character in order to improve her art. Photo courtesy of Cuiying Zhang

“Artists can paint good works only after their hearts are cleansed through cultivation,” says Cuiying Zhang, one of the world’s preeminent classical Chinese painters.

Zhang’s journey speaks through the rice paper on which she paints — a lifetime of learning, hardship and heroism, stripping her of humanity’s unwanted weights, revealing the soul of a culture too few remember but adore when they do.

Beatrix, former Queen of the Netherlands, Naruhito, Crown Prince of Japan, Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, and Leonid Kuchma, former president of Ukraine, are among Zhang’s popular patrons, each inspired by her universal stroke of genius that makes us simultaneously more human, divine, alive.

And now, Zhang’s fight to save innocent lives — a mission that risks her own — paints a picture of who she really is and how she’ll be remembered long after the paint on her rice paper dries.

First master

Zhang wasn’t born a master, though destiny’s diamonds of determination, artistic dexterity, and direction did clearly provide a path for her to follow.

“I was quite famous in my neighbourhood,” says Zhang, the aptly nicknamed “crazy little painter,” born in Shanghai. “I never played with other children outside. My only interest was painting at home.”

At age 4, Zhang was already impressing people with her paintings — one in particular who would change her life forever. This art teacher at school recognized the little girl’s unique gifts and decided she needed the mentorship of a master equally charmed. So the teacher introduced Zhang to a master of traditional Chinese painting, 70-year-old Mr. Zicheng Shen, who taught her much more about art than painting.

“Mr. Shen was indifferent to fame and fortune,” Zhang says of her most influential teacher, who treated her like a daughter. “My family was not rich, but he taught me without asking any money, just because he thought I was born with superb spirit and had a pure heart for painting.”

Mr. Shen trusted his young student, lending her paintings he’d painstakingly copied from ancient masterpieces. Zhang reveled in her assignments copying the works of past masters, such as Kaizhi Gu’s Nymph of the Luo River, Hongzhong Gu’s Night Revels of Han Xizai, and Shitao’s landscapes.

“Mr. Shen showed me every stroke at that time,” Zhang says. “He was particular about the light and dark, and the twists of every stroke.” Shen’s tutelage was not simply classical in style, his method was truly traditional. Many of China’s most famous artists through history cultivated Buddhahood or the Tao, understanding that the pursuit for artistic perfection began first with refining themselves.

“You need much patience, concentration, and a tranquil mind to make a good painting,” Zhang says, recalling her teacher’s wisdom. “Otherwise, people will sense the ‘temper’ in the painting.”

Over a decade, Shen and Zhang formed a bond so strong even a war couldn’t break it. During the Cultural Revolution — literally a war on 5,000 years of China’s traditions and art — Shen was exiled to the countryside of Suzhou. But that didn’t deter Zhang from visiting him by train several times a month to continue her study.

In Tranquil Gaze, Calm Thoughts, Zhang’s ethereal ability to depict grace and elegance illustrates well her own honourable life and character.

Zhang studied with one of the last living masters of classical Chinese painting, who taught her landscape painting was intimately tied to the artist’s inner journey, a concept well-illustrated in her Ethereal Heaven and Water.

By her 20s, Zhang was drawing praise from masters as significant as her own. Juntao Qian, a famous Chinese artist in his 90s known for seal carving, calligraphy, and Chinese painting, heralded her as one of China’s most promising talents.

“Her paintings combine the subtlety of wind, rain, dimness, brightness, and everything in the world,” said Qian. “She understands well the principles of nature and has obtained the essence of the ancient people.”

The venerable artist described her landscape paintings as having a quality of “transcending delight,” comparing her to Wei Wang, the revered eighth-century poet and landscape artist, and Tong Guan, the legendary landscape painter of the Northern Landscape style during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Taking flight

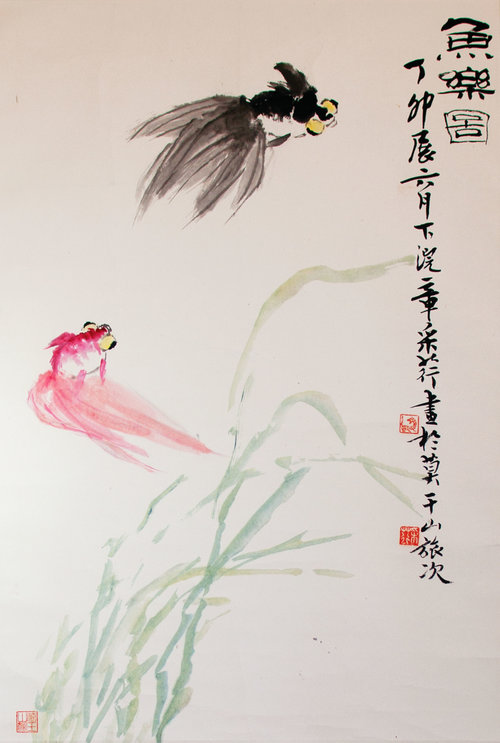

Though the form of the goldfish in Light-hearted isn’t realistic like a Western classical painting, what is true is their spirit and personality — the aim of classical Chinese painting.

In 1990, Zhang immigrated to Australia with her husband and daughter, excited to get away from the environment now so far removed from the morality her mentors instilled in her.

“The atmosphere in the art field in China was already very bad,” she says. “Artists schemed and fought against each other for fame and profit, but I couldn’t.” The quietude of her new home inspired a peaceful mind and space for painting. But her serenity would soon be smashed, challenging her physically, mentally, spiritually.

At the young age of 30, Zhang suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, a condition where the immune system attacks the lining of hundreds of joints.

“It was difficult for me to walk, and I could not sit for long,” says the artist. “I could only lie at home, unable to paint. I felt like I was just living death. My art career started so early but then ended so early.”

Desperate, struggling, Zhang visited all the famous Chinese and Western doctors in Sydney, but none could help. With a stroke of luck — or a touch of fate, as the case may be — her husband returned home one day with a boon.

“I still remember when my husband came home that day — he was very excited,” she says. He explained that a new form of qigong — a cultivation system refining morality in combination with tai chi-like exercises — was being taught in town. “I didn’t believe in qigong at that time, but it sounded marvelous.”

The practice, called Falun Gong, hit home

Pure Lotus is Zhang’s self portrait while doing Falun Gong, the spiritual discipline that cured her painful ailment that prohibited her from painting.

“When I listened to the principles, I was immediately attracted,” says the master painter. “I felt many of the principles were like what Mr. Shen taught me, such as to gain, you must suffer losses, and don’t pay much attention to fame and profits. I felt that they were such good principles.”

When she practiced the first exercise, she says, “I felt my occluded vessels were cleared. After I went home, I was even able to sit.”

Nine days later, when the workshop ended, a new chapter in her life began. “I really walked as though I was flying,” Zhang says, her rheumatoid arthritis completely healed. “It was just so miraculous.”

Not only could Zhang paint again, she finally unraveled a deeper essence of art.

“In history, the best works in Chinese painting were called ‘divine works.’ After practicing Falun Gong and following its principles of truthfulness, compassion and tolerance, I could understand the meaning behind those ancient paintings,” she says. She more tangibly experienced that, as artists let go of fame, gain and fortune, their spirits would ascend higher, transforming their perspectives, and consequently, each brushstroke.

But again, a storm would come that she’d have to weather with every ounce of her will.